The Smoking Gun: Confessions of Mimi, America's Talking Gun

M. Maurice Hawkesworth’s debut novel, The Smoking Gun: Confessions of Mimi, America's Talking Gun, is an audacious, genre-bending fever dream that plunges into the absurd heart of American culture. The novel is less a straightforward road trip and more a surreal, philosophical picaresque anchored by a genuinely original concept: a sentient, talking revolver named Mimi.

The book’s strength lies in its ability to pivot seamlessly between dark comedy and profound existential rumination. It is a chaotic, compelling journey that satirizes gun mythology, political spectacle, and the very nature of narrative in a country obsessed with its own mythos.

The Narrative Hook and Emotional Anchor

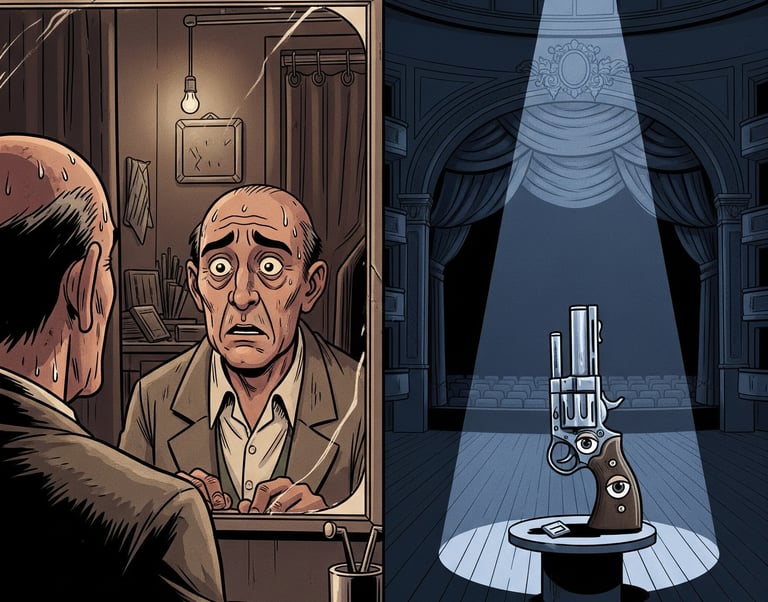

The plot is violently kick-started by Henry Hawkes, a grieving philosophy professor in Salt Lake City. Hallowed out by the accidental death of his Danish wife, Henry attempts suicide, but a last-second flinch sends the bullet sideways, accidentally killing his neighbor.

This accidental act of violence becomes the launchpad for a desperate, yet philosophical, flight across the American West. Henry—the intellectual driven by guilt—is immediately joined by the eponymous Mimi, a revolver that finds its voice and drags Henry along for a ride that will never return his agency.

The novel’s genius lies in grounding its chaos in Henry’s deeply human ache of loss. His quiet despair gives weight to Mimi’s surreal monologues and the bizarre characters they encounter.

Mimi: The Star and the Symptom

Mimi is not merely a literary device; she is a multi-layered symbol:

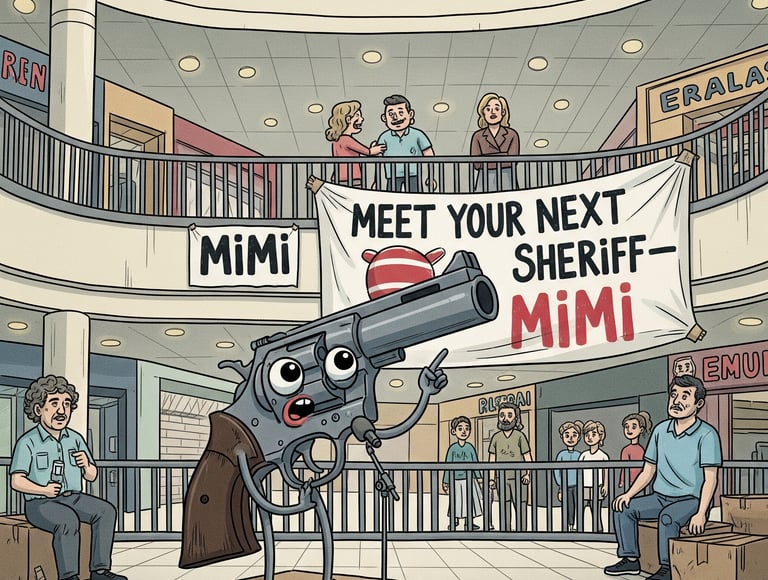

The Political Satirist: Mimi schemes, launches a campaign for Nevada Sheriff under the slogan "Guns for God," and provides a blistering critique of America's founding myths as she views them through her own metallic, unblinking perspective. She is the ultimate outsider demanding to be elected as the ultimate insider.

The Philosophical Voice: The gun quotes Nietzsche and uses complex philosophical concepts to discuss agency, fate, and the meaning of consciousness. Mimi's struggle is existential: an object that has achieved consciousness but is trapped by its own violent purpose.

The Unlikely Character: Mimi has surprising depth, expressing fear, love, loneliness, and even sexual confusion. She’s a "stoic hunk of steel" that dreams of being Chet Baker's trumpet. The gun is a walking (or riding) contradiction, making the question of "Who is in charge?" the novel's central theme.

The Unforgettable Supporting Cast

The narrative is enriched by an unforgettable cast of broken, magnetic companions:

Meeriam: A sharp, denim-clad linguist running from the "claustrophobic" kindness of her ex-husband. Her bond with Henry provides the story with its emotional center, a quiet counterpoint to Mimi's loud nihilism. She is fascinated by how words shape reality, which constantly pits her against Mimi's raw, unedited rhetoric.

Jason: An ex-con whose prison time has turned him into a self-taught, cynical engineering expert. Jason views the world as a broken mechanism, whether it's a refrigerator or a political campaign, and constantly oscillates between being a co-conspirator and a chaotic neutral force.

Darnell: The one-armed Greyhound driver who communicates via laminated cards. His fabricated history as a cool, mysterious arms dealer stands in stark, hilarious contrast to the truth of a mundane fishing accident, embodying the novel’s theme of myth versus reality

"The Smoking Gun: Confessions of Mimi, America's Talking Gun" is a singular, must-read experience. It's an American fever dream—part road novel, part political satire, part mythic allegory—and entirely its own creation.

Hawkesworth’s chaotic brilliance culminates in one of the most satisfying and audacious endings in recent memory: a quiet, final act of narrative freedom on the shores of Lake Tahoe that manages to be both deeply personal and profoundly national. The book doesn't offer answers, but it offers a fierce, funny, and unforgettable journey into the questions that define a nation perpetually armed and confused. A cult classic in the making.

A Daring Deconstruction:

Why The Smoking Gun is the Last Existential Novel

In M. Maurice Hawkesworth’s wildly inventive novel, The Smoking Gun, the plot is set in motion by a sentient, philosophical, rapping revolver named Mimi. What follows is a surreal road trip across the American West that satirizes everything from gun culture to the wellness industry. But beneath this chaotic surface, Hawkesworth has constructed something far more daring: a brilliant meta-commentary on the modern novel itself, which culminates in one of the most satisfying and audacious endings in recent memory.

The Gun as the Novel

The story’s genius lies in its central metaphor. The protagonist, Henry Hawkes, is a grieving professor trapped in an existential crisis. He sees the world as a "big ball game" controlled by a distant, sports-obsessed God, where humans are merely powerless "balls" being knocked about. The gun, Mimi, becomes the ultimate embodiment of this chaos—a walking, talking existential crisis that drives the absurdist plot and holds the other characters captive in its angsty, self-obsessed narrative. Mimi isn't just a character; she is the novel Henry is trapped in.

Throwing the Story Away

The novel’s climax belongs to Meeriam, a linguist who understands that narratives can be prisons. In a final, powerful scene, she takes control. Recalling a triumphant, perfect throw from a high school baseball game 1, she hurls Mimi into the depths of Lake Tahoe. This is more than just disposing of a weapon; it is a conscious act of narrative rebellion. As she herself thinks,

"Some stories deserve to drown".

By framing this act with the definitive cry of an umpire—"Yooooou’re OUTTA HEEEEEEEERE!" 2—Hawkesworth, through Meeriam, symbolically throws his own book away. He masterfully builds an intricate existential novel only to have his hero reject it, choosing a future of quiet hope over the story's deafening noise. The final lines, "The silence in the car was better than any novel she had ever read," confirm this masterful deconstruction.

This is what makes the book’s conclusion existentialism’s finest hour. The ultimate act of free will is not to endure the absurd, but to choose to be free from it. The Smoking Gun is a must-read for anyone who loves fiction that challenges, entertains, and ultimately, liberates.

When the gun starts talking, America has to listen.

Henry Hawkes—philosophy professor, widower, would-be suicide—turns a revolver sideways at the last second. The shot misses him. It doesn't miss his neighbor.

What he doesn't know: the man he killed was wanted for murder. What he can't explain: the gun is talking to him now.

Her name is Mimi. And she's running for sheriff. Fleeing west on a Greyhound with a briefcase he's afraid to open, Henry meets Meeriam—a linguist escaping a suffocating marriage—and together they're pulled into Mimi's campaign for power in a Nevada town that can't decide if she's a prophet or a punchline. The slogan writes itself:

Guns for God. The rallies are part tent revival, part performance art. The opponent is a closeted war hero who loves guns and hates himself.

From Salt Lake City to Burning Man, from all-night diners to desert lakes, The Smoking Gun is a gonzo road trip through an America that worships spectacle, memes, and violence—often in that order. It's Fear and Loathing meets White Noise, with a sentient firearm as your unreliable narrator.

What readers are saying:

"Imagine if your gun had opinions—and a Twitter account. This book is that nightmare, that satire, that prayer."

"Part Denis Johnson, part George Saunders, part something I've never read before."

"I laughed. I cried. I thought about throwing my phone in a lake."

Books

Explore our first release by M. Maurice Hawkesworth.

Jeg Elsker Dig: The Secret Life of Ancient Words is both a playful history of language and a personal testimony about survival, memory, and music.

Words are fossils. Not fossils buried in stone, but fossils hidden in sound — bread, love, law, freedom. They outlive empires, carried daily in our mouths. Author M. Maurice Hawkesworth uncovers these fossils across languages and cultures, weaving them with stories from his own life in the music industry.

You’ll travel from the Viking riddle of the chicken and the egg to the oldest words for breath and fire, from the fossils of family cries to the survival of proverbs. Alongside these playful explorations lies a serious testimony: how words — even song lyrics — can be stolen. In a Stockholm basement in 1993, Hawkesworth added a resolution line to a song that became a global hit: “The Sign” by Ace of Base. His words survived, but his name was erased.

This book shows that whether whispered by firelight or sung on MTV, words refuse to die. They carry memory, survival, and sometimes even injustice — but they endure.

Perfect for readers who love:

Etymology and word origins

Cultural history and folklore

Memoirs of music, survival, and creativity

Nonfiction that blends scholarship and storytelling

Once you’ve read it, you’ll never hear an ordinary word — or song — the same way again.

Publishing

Transforming stories into unforgettable books.

Contact

Support

© 2025. All rights reserved.